Developments in Living Arrangements and Choice for Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

Introduction

Having opportunities for choice is an important component of self-determination, the ability of a person to make decisions about the parts of life that person wants to control (Abery & Stancliffe, 2003). More specifically, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) have unique challenges to exerting choice and control over their lives. While there has been a big shift in where people with IDD live over the last 40 years, from large institutions to smaller and more individualized settings, their opportunities to make choices are still limited in some ways. This policy brief explores the changes in living arrangements and opportunities to make choices over time as well as the relationship between the two.

This research utilizes data from Residential Information Systems Project (RISP) reports from 1997-2014 and National Core Indicators-Adults Consumer Survey (NCI-ACS) from 2007-2015 to address changes in living arrangements and choice over time for people with IDD. We looked at two types of choices from the NCI data. Support choice was based on whether participants had a choice about where and with whom they would live, where they went during the day, who their case manager was, and who their staff was. Therefore, support choices relate to key life issues that are context and service related. Everyday choice was based on whether participants had a choice about their daily schedules, how they spent their free time, and how they used their spending money. Therefore, everyday choices relate to day-to-day aspects of life of a more personal nature. Choice was based on two scales from 0-2 with 0 representing no choice, 1 representing choice with some help, and 2 representing the person having full choice. The choice scales were created by Lakin et al. (2008) and Tichá et al. (2012) using factor analysis and Cronbach’s Alpha to identify choice items that reflect the constructs of support and everyday choice. Both scales were calculated as an average of all the selected items.

This publication was funded by the following grant: NIDILRR FIR #90IF0101-01-00.

What has changed over the past 10 years regarding where people with IDD live?

A study by Woodman, Mailick, Anderson, and Esbensen (2014) shows that the number of persons with IDD who live in small residential settings has increased significantly from 1988 to 2011, which means that persons with IDD are more included in society. Persons with IDD feel more supported and have greater self-determination in community-based settings (Woodman et al., 2014). As a result of ADA mandates, states have eliminated many institutional settings and opened more community residential settings for people with IDD (Francis, Banning, & Turnbull, 2014).

The number of persons with IDD who live in large institutions (16 or more people) has plummeted since 1977, while the number of persons living in small residential settings has significantly risen (Larson & Lakin, 2012). While there are still people with IDD living in large institutions in 37 states (Jones & Gallus, 2016), a Residential Information Systems Project (RISP) report shows that in 2015 there were nearly 2 million adults with IDD living in noninstitutional settings. Even though these large institutions were still in operation, nineteen of them across nine states were closed or planning to close between 2012 and 2015 (Larson et al., 2012, Jones & Gallus, 2016). By June 30, 2014, 14 states had closed all of their state-operated IDD facilities serving 16 or more people (Larson, Eschenbacher, Anderson, Taylor, Pettingell, Hewitt, Sowers, & Fay, 2017).

Residential Information Systems Project (RISP, Larson, et al., 2017) has found the number of people with IDD who receive supports and services from a state IDD agency living in institutions of 16 or more people decreased by 80% from 1977 to 2015, while the number of people living in small residences (6 or fewer people) increased by over 1,900% over this same time period (See Table 1). In the last 20 years, the number of people with IDD who receive supports and services from their state while living in the home of a family member has also increased by 135%.

| Year | Home of a Family member | 1-6 Person Setting | 7-15 Person Setting | 16+ Person Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | N/A | 20,400 | 20,024 | 207,356 |

| 1987 | N/A | 69,933 (+243%) | 48,637 (+143%) | 137,103 (-34%) |

| 1997 | 296,946 | 194,968 (+179%) | 53,914 (+26%) | 93,362 (-32%) |

| 2007 | 552,559 (+86%) | 316,291 (+62%) | 58,920 (+9%) | 62,496 (-33%) |

| 2015 | 698,556 (+26%) | 413,852 (+38%) | 56,627 (-4%) | 42,490 (-32%) |

Adapted from the RISP FY 2015 report (Larson et al, 2017).

N/A: Not applicable. Data on the number of people with IDD receiving long term supports and services while living in the home of a family member was not available for 1977 and 1987.

What has changed over the past 10 years in how people with IDD make choices for themselves?

Past studies have shown that persons with IDD have control over smaller, everyday choices, such as choosing their clothing, yet they are not given as many opportunities to make support-related choices, such as where they live, who their roommates are, and which types of medical care they receive (Wehmeyer & Metzler, 1995; Heller et al, 1999; Heller, Miller, Hsieh, & Sterns, 2000).

Previous research has also shown that, in general, persons with IDD rarely choose where and with whom to live (Stancliffe, et al., 2011). The opportunity for people with IDD to make these choices decreases as their level of intellectual disability increases (Stancliffe, et al., 2011).

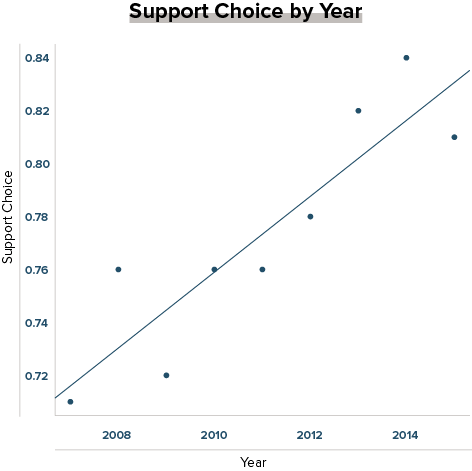

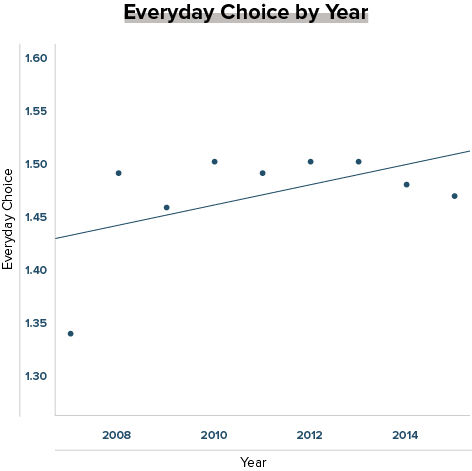

Figure 1 below illustrates the results from the NCI data from 2007-2015 regarding two kinds of choice: support-related and everyday choice. Support choices increased significantly over the years, while everyday choice did not. Note that everyday choices were significantly higher than support choices across all years and closer to 2, the maximum average choice possible in NCI data, which supports previous research on the difference between these two types of choices.

Does where people with IDD live make a difference in the amount of choice they have?

Even though people with IDD have moved from large institutions to smaller residential settings, their opportunities for making choices are still very limited (Heller, Miller, & Hsieh, 2002). Previous research has shown that persons with IDD who live with small groups of people (4-6) experience limited options for making choices for themselves and consequently have a lower quality of life (Wehmeyer et al., 1998). In contrast, persons with IDD who live in individualized community settings, e.g. independent apartments, have more opportunity to make choices than persons with IDD who live in group settings (Stancliffe, et al., 2011). Persons with IDD who live in non-institutional, community-based settings have more opportunities to make everyday choices than those who live in institutions (Lakin, et al., 2008). Further, persons with IDD who live in individualized community settings more often make support-related choices, such as choosing where and with whom to live, than persons with IDD who live in group settings (Stancliffe, et al., 2011).

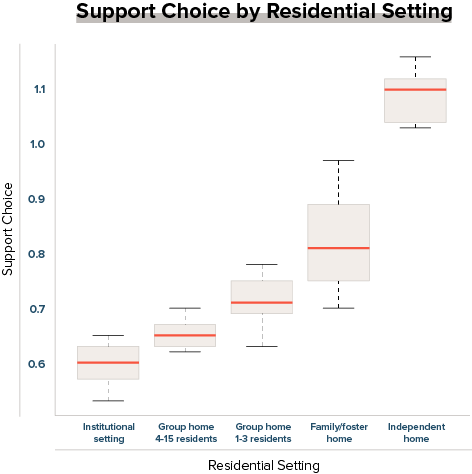

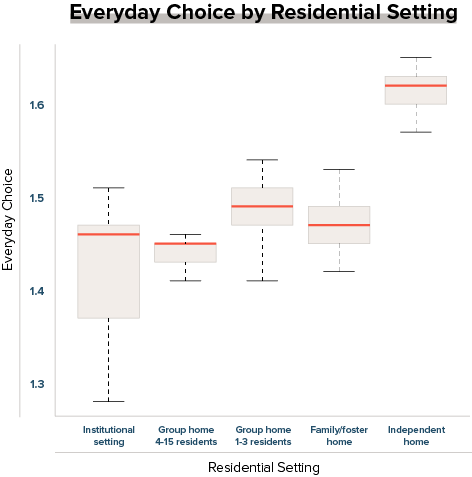

Figure 2 below shows the difference in support related and everyday choices by residential setting based on the NCI data. The red lines are the average choice scores within each setting. The bigger the box, the more variability in scores. Support choice showed significant increases for many of the comparisons, except for between institutional settings and group homes with 4-15 residents and between group homes with 4-15 residents and group homes with 1-3 residents. For everyday choice, people in independent settings expressed having significantly more choice than those in all other settings, while the choice expressed by those in all non-independent settings was comparable.

Note: Means for each year and residential setting are adjusted based on age, level of intellectual disability, mobility, behavioral support needs, mental health diagnosis, autism diagnosis, verbal communication ability, visual/hearing impairments, and the proportion of choice items answered without a proxy.

Current Policy Initiatives and Progress

At the federal government level, in 2014 the Administration on Community Living in the US Department For Health and Human Services promoted supported decision making (SDM) by funding the National Resource Center for Supported-Decision Making, a training center located in Washington, D.C. (Shogren et al., 2017).

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also passed the Community Rule in January of 2014, protecting the rights of persons with IDD who receive Home and Community Based Services (HCBS). This law ensures that persons with IDD receiving HCBS have the right to choose where and with whom they live, what they do in their leisure time, and the services and supports they receive (Medicaid Program HCBS, 2014). Each state has until 2022 to fully transition to these standards, and each state Medicaid agency is required to establish a plan that describes how they will accomplish this by that date.

In an effort to increase SDM for people with IDD in Texas, in 2009 the state Legislature authorized and funded a pilot program that involved volunteers who were trained to help people with IDD in making support-related choices (Shogren et al., 2017). In 2013, after the pilot program had expired, Texas amended its guardianship law to require more evidence to prove that persons with IDD cannot make choices with SDM before appointing a guardian (Shogren et al., 2017). Texas is the only state that has authorized a law for SDM as of 2017.

Conclusions

Over the last forty years, a significant number of persons with IDD have moved from institutions to smaller residential settings. With this transition, their level of support-related choice has steadily increased. Everyday choice has remained consistent over the time period we analyzed, but it is overall higher than support choice.

Regarding the relationship between residential setting and choice across the years, the best predictor of more choice for both types consistently were settings of an individual or independent nature (e.g. living outside a group, foster, or family setting).

For support choice, there was also a significant increase in choice for those living in family settings over group homes of any size and institutional settings. Further, there was significantly less support-related choice for those living in institutional settings compared to all other settings. It is interesting that for everyday choice there was no significant difference between institutional, group, or family settings.

Suggested Citation

Houseworth, J.,Tichá, R., Smith, J., & Ajaj, R. (2018). Developments in living arrangements and choice for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Policy research brief, 27(1), University of Minnesota, Institute on Community Integration.

Related Resources

References

Abery, B. H., & Stancliffe, R. J. (2003). A tripartite-ecological theory of self-determination. Theory in self-determination: Foundations for educational practice, 43-78.

Alba, K., Bruininks, R., Lakin, K. C., Larson, S., Prouty, R. W., Scott, N., & Webster, A. (2008, August). Residential Services for Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Status and Trends Through 2007 (Publication). Retrieved November 3, 2017, from Research and Training Center on Community Living Institute on Community Integration/UCEDD website: https://rtc3.umn.edu/risp/docs/risp2007.pdf

Blanck, P., & Martinis, J. G. (2015). “The right to make choices”. The national resource center for supported decision-making. Inclusion, 3(1), 24-33. doi:10.1352/2326-6988-3.1.24

Francis, G. L., Banning, M. B., & Turnbull, R. (2014). Variables Within a Household That Influence Quality-of-Life Outcomes for Individuals With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Living in the Community: Discovering the Gaps. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 39(1), 3-10. doi:10.1177/1540796914534632

Heller, T., Miller, A. B., & Factor, A. (1999). Autonomy in Residential Facilities and Community Functioning of Adults With Mental Retardation. Mental Retardation, 37(6), 449-457. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(1999)037<0449:airfac>2.0.co;2

Heller, T., Miller, A. B., & Hsieh, K. (2002). Eight-Year Follow-Up of the Impact of Environmental Characteristics on Well-Being of Adults With Developmental Disabilities. Mental Retardation, 40(5), 366-378. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040<0366:eyfuot>2.0.co;2

Heller, T., Miller, A. B., Hsieh, K., & Sterns, H. (2000). Later-Life Planning: Promoting Knowledge of Options and Choice-Making. Mental Retardation, 38(5), 395-406. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2000)038<0395:lppkoo>2.0.co;2

Jones, J. L., & Gallus, K. L. (2016). Understanding Deinstitutionalization. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41(2), 116-131. doi:10.1177/1540796916637050

Lakin, K. C., Doljanac, R., Byun, S., Stancliffe, R., Taub, S., & Chiri, G. (2008). Choice-Making Among Medicaid HCBS and ICF/MR Recipients in Six States. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 113(5), 325-342. doi:10.1352/2008.113.325-342

Larson, S.A., Eschenbacher, H.J., Anderson, L.L., Taylor, B., Pettingell, S., Hewitt, A., Sowers, M., & Fay, M.L. (2017). In-home and residential long-term supports and services for persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities: Status and trends through 2014. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Research and Training Center on Community Living, Institute on Community Integration. Access at https://risp.umn.edu/publications

Larson, S., & Lakin, C. (2012). Behavioral Outcomes of Moving From Institutional to Community Living for People With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: U.S. Studies From 1977 to 2010. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37(4), 235-246. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

Larson, S.A., Eschenbacher, H.J., Anderson, L.L., Taylor, B., Pettingell, S., Hewitt, A., Sowers, M., & Bourne, M.L. (2017). In-home and residential long-term supports and services for persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities: Status and trends through 2015. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Research and Training Center on Community Living, Institute on Community Integration. Access at https://risp.umn.edu/publications

Medicaid Program; State Plan Home and Community -Based Services, 5 -Year Period for Waivers, Provider Payment Reassignment, and Home and Community -Based Setting Requirements for Community First Choice and Home and Community -Based Services (HCBS) Waivers, Federal Register § Section 1915(k), Section 1915(c) et seq. (2014).

Residential Services for Persons with Developmental Disabilities: Status and Trends Through 1997 (Publication No. 51). (1998, May). Retrieved November 3, 2017, from Research and Training Center on Community Living: Institute on Community Integration/UAP website: https://rtc3.umn.edu/risp/docs/risp1997.pdf

Shogren, K., Wehmeyer, M., & Singh, N. (2017). Handbook of positive psychology in intellectual and developmental disabilities translating research into practice (Springer series on child and family studies). Cham: Springer.

Stancliffe, R., Lakin, K., Larson, S., Engler, J., Taub, S., & Fortune, J. (2011). Choice of living arrangements. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(8), 746-762. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

Tichá, R., Lakin, K.C., Larson, S., & Stancliffe, R., Taub, S., Engler, J., Bershadsky, J., & Moseley, C. (2012). Correlates of everyday choice and support-related choice for 8,892 randomly sampled adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities in 19 states. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(6), 486-504.

Wehmeyer, M., & Schwartz, M. (1998). The Relationship Between Self-Determination and Quality of Life for Adults with Mental Retardation. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 33(1), 3-12. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

Wehmeyer, M., & Metzler, C. (1995). How Self -Determined Are People With Mental Retardation? The National Consumer Survey . Mental Retardation, 33(2), 111-119. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

Woodman, A. C., Mailick, M. R., Anderson, K. A., & Esbensen, A. J. (2014). Residential Transitions Among Adults With Intellectual Disability Across 20 Years. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 119(6), 496-515. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-119.6.496