Person and Family-Centered Approaches in Mental Health and Co-occurring Disorders Online Training Lesson #4: Support for Relationships and Valued Social Roles

Welcome to the Minnesota Department of Human Services Online Training Program in Person and Family-Centered Approaches in Mental Health and Co-Occurring Disorders

Training Program Description: This training program is designed for professionals in the mental and chemical health community. It may also be useful to others with interested in supporting people with mental health conditions to live well. This training program supports learners in understanding the value in trends toward person and family-centered approaches in Minnesota. It provides context to this movement that is Minnesota specific and helps learners support the vision the Minnesota Olmstead Plan. The content provides both context and enhanced skills in these approaches and practices.

Directions: Please scroll down or click on the page on the menu to see additional content in the lesson.

The following lessons are included in this training program:

- Lesson #1: The Context of Person and Family-Centered Practices in Mental Health Services in Minnesota

- Lesson #2: The Journey to a New Vision

- Lesson #3: Cultural Responsiveness

- Lesson #4: Support for Relationships and Valued Social Roles

- Lesson #5: Supporting People with Mandated Services and Choice Limits

- Lesson #6: Individual Practices that Support Person and Family-Centered Approaches

- Lesson #7: Organizational Practices that Support Person and Family-Centered Approaches

- Lesson #8: Engaging in System and Community Level Changes

A Note about Language: This training program recognizes that the terms mental health professional and mental health practitioner are recognized titles have specific meaning related to scope of practice within the Minnesota mental health system. However, for the purposes of this training, the terms practitioner or professional are used interchangeably to indicate any person with professional responsibilities in the system. This includes clinical professionals such as psychiatrists. It also includes social services professionals such as case managers or peer specialists. If a specific role or scope of practice is important to content, that is made clear in content.

Page 1

Narration for this page

Support for Relationships and Valued Social Roles

“Unique paths should include the opportunity to earn some money not just use up time.”

- Co-Creation group member, Mahnomen, MN

“How do we navigate a system in a family-centered way that’s designed so [siloed] and individualistic?”

- Co-creation group member-St Paul, MN

“Viewing people as broken ruins the relationship.”

- Co-creation group member-New Brighton, MN

“[Consider] how difficult it is to feel included, valued and I have power due to past experiences.”

- Co-Creation group Member-Rochester, MN

"Family maybe should be 'supports'? My 'family' is not biological.”

- Participant, American Indian Mental Health Conference, 2017.

Page 2

Narration for this page

Welcome!

Here is a description of the lesson you are starting:

Mental health professionals do not always consider people’s relationships and having valued social roles as part of recovery. They also rarely acknowledge that family caregiver isolation can occur. When they do get involved with families, it is usually to sort out family conflict. However, this limited approach means that the person is not supported in developing and maintaining relationships. They may miss out on participation of social roles that make life meaningful. It means that families may be excluded from recovery efforts. It often means the family may not have their own needs met. This lesson is an overview of why relationships and valued social roles are important parts of person and family-centered recovery practices. It provides strategies for working with individuals in the context of family, social roles, and other relationships.

Learning Objective

After completing this lesson, you will be able:

- Implement strategies for working in the context of relationships, family, and valued social roles.

Page 3

Narration for this page

Importance of Valued Social Roles and Relationships

Having relationships and valued social roles are important to recovery and resilience. The words “valued social roles” means that people are included in social groups that are meaningful to them. These roles should increase their social capital. Social capital is about being known and having mutuality in relationships. Views on valued social role will vary based on culture, age, and life experience.

Reflection Activity

Directions:

Listen to the following voice clips. Write your responses in to the following questions. Open the PDF on the eight dimensions of wellness to complete this activity.

- List out all the social roles you heard that were valued by the individuals in these stories. Did they value the same things?

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) publishes eight dimensions of wellness. Many of these areas embrace the need for strong relationships. They indicate the need for being positively connected to community through valued social roles. Open the PDF and review the eight dimensions. Which of these did you hear reflected in the voice clips? Write out the number of the dimension and describe what you heard that connected to that dimension.

- Employment is a natural place for being valued and making social connections. In listening to these stories what did you hear about employment? Is employment the only or most important way to stay connected? Do you think the type of job matters when considering valued social roles? Why or why not?

Page 4

Narration for this page

Person and family-centered practices are rooted in relationships, inclusion, and belonging. This aligns well with wellness and recovery models in mental health.

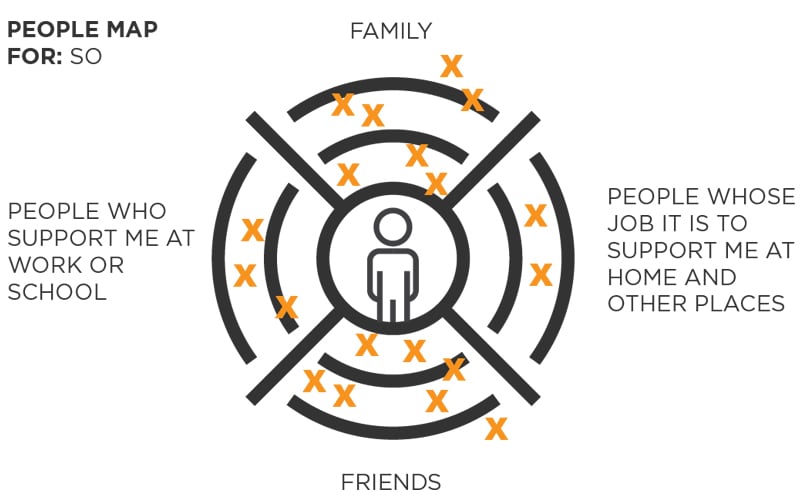

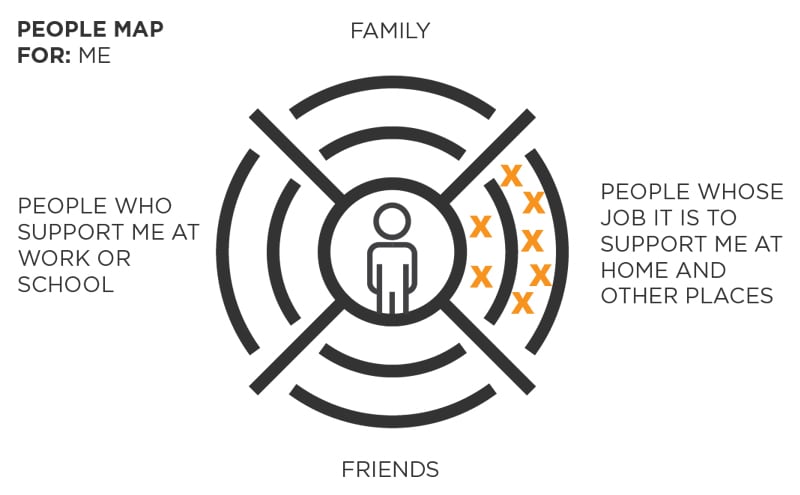

Directions: Relationships maps are often used in person and family-centered plans. This includes the Person-Centered Thinking training currently available in Minnesota. Review the images of relationship maps on this page. One is a map of a person who does not receive services. The other is of a person who has been in and out of services multiple times. Can you tell the difference? How?

Page 5

Narration for this page

Considerations to Supporting Relationships and Valued Social Roles

Directions: Click on the items below to learn more about the considerations in supporting relationships and valued social roles. Which of these can you relate to? How do you address these barriers in your work.

Page 6

Narration for this page

These conversations help define recovery.

Using Relationships and Roles as Measures of Success

Understanding the person’s values and desires as they relate to social roles and relationships helps define a meaningful recovery. It’s important to consider inclusion and satisfactory relationships and roles as measure of success in treatments and services. If people are not less isolated what is the point of treatment or services? Professionals may explore how and if the person wants to engage supporters in treatment plans and recovery activities. They can explain the value of educating and supporting family through recovery. This can include all members including children who are often forgotten.

It is important to be cautious not to give advice or share personal opinions about the quality of a person’s relationships. These opinions may encourage people to distance themselves from their supporters. This can lead to estrangement and a loss of supports. It could also lead the person to be less honest with the professional. If relationships are complicated, it’s a good opportunity to help people learn the skills they need to navigate them. This is part of moving toward wellness and recovery.

Page 7

Narration for this page

Strategies –Holding Hope – A Person and Family-Centered Approach

Comments by professionals can have a strong impact on people. They can help people feel more hopeful or less hopeful. By staying focused on the person’s goals and recognizing the importance of relationships and valued social roles, professionals can help people move forward. Try the activity below.

Directions: This is a matching exercise. Click a “statement” to select it, and then click an “answer area” to try and get a successful match. Keep trying until you successfully match each “statement”.

Page 8

Narration for this page

Strategies - Expanding Existing Professional Skills and Approaches

Mental health professionals often have a number of existing skills and approaches that help them with supporting relationships and roles. They may need to adjust how these things are applied. For example, both diagnostic and functional assessments look at social functioning and relationships. Current practices may be deficit-based or focus on stress or loss. Taking time in your assessments to find out people’s strengths and hopes can be useful to developing a recovery plan.

Motivational interviewing skills can be used to explore places where people feel ambiguous or unclear. When asking about supporters don’t confine your questions to “family”. Use more global terms and questions like: “Do you live with anyone? Do you have anyone in your life you can count on to be there for you? What does this person/people do for you?” “Are there people in your life who count in you?” This is a more culturally open way of understanding these roles. Encourage the person to ask supporters what might be helpful to them. This helps the person remember to give back support to those that are there for them.

Page 9

Narration for this page

Collaboration and communication may be more frequent in person and family-centered approaches.

Strategies - Trying New Professional Skills and Approaches

Person-centered thinking practices (PCT) are something the state has adopted to help professionals think differently about services and supports. There are a number of approaches in that training that support problem-solving and learning for the purpose of being more person-centered. You’ve already seen the relationships map. Other skills and tools include the process of reflecting on what’s working or not in relationships and roles. This can be helpful for clarifying what is happening right now that needs to change. Another approach is called the 4+1 questions, which is a process of examining what has been done for the purpose of deciding what to do next. Another is a learning log. This can be helpful for understanding things that people may have trouble articulating in an organized way.

As people have used these approaches they have found that their roles may often include more collaboration between professionals in order to make progress. Being willing to learn and try new things can be important to person and family-centered practices.

Page 10

Narration for this page

Strategies- Rethink Privacy and Confidentiality Practices and Supporters

As mentioned previously, social services has tended to be stricter in their approach to privacy and confidentiality than mainstream medical care. This is especially true in how family and close natural supporters are engaged. These practices can keep families from being able to support their family member effectively. It can leave the person without natural support that many of us have. These practices can reinforce stigma and shame around these illnesses. It can send the message that people with mental illness or substance abuse disorders are not worthy of the same types of social and family support as people with other types of illnesses.

It can sometimes be easier to think about mental health concerns around privacy by comparing them practices in physical health when people are facing serious or chronic illnesses. It’s common in physical medicine to ask people to bring a supporter with them to appointments. They may know of resources for families like support groups or education programs. In a medical emergency, family is often seen as a valuable resource. By conveying this to people receiving services, they may become less fearful of sharing their needs and acknowledging the needs of their family.

Page 11

Narration for this page

Being with peers and looking at a future with hope can be powerful.

Formal Person and Family-Centered Planning to Support Social Roles and Relationship

A more formal planning process can be helpful when people or their families have depleted their networks. There are a variety of person and family-centered planning processes that can be of help. Mental health professionals and practitioners should be familiar with different forms of person-centered planning. They should have information and referrals for people and families who may find this helpful. One person and family-centered planning process in that comes from the mental health field is called Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP®). WRAP® can be used with individuals, families, and organizations. Planning Alternative Tomorrows with Hope (PATH) comes from the community of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities but has been use in many settings including with individuals from various walks of life. It also works for families and organizations. It helps to set a positive vision and create steps toward it. The skills learning in the Person-Centered Thinking (PCT) training in Minnesota can be applied to planning in a process called Picture of a Life (POL). You can find more information in the resources section of this training program.

Keep in mind, a formal plan belongs to the person or the family (not the professional). They are not obligated to share any part of the plan with professionals. However, whether they share them or not, these plans can be powerful for people and help them be better advocates in managing treatments and supports.

Conclusion and Review

Narration for this page

Conclusion

This lesson was meant to help you achieve the following learning objective:

- Implement strategies for working in the context of relationships, family, and valued social roles.

Lesson Review

In this lesson you learned:

- A person’s relationships and valued social roles are a critical consideration on the road to recovery and wellness.

- It is important that professionals take time to learn about each person’s perspective on relationships and where they find value and meaning in life.

- People should be encouraged to include significant supporters appropriately in treatment and recovery plans.

- People’s satisfaction with the quality and quantity of relationships and roles they have should be part of assessing treatment success and usefulness of services and supports.

- It is important to remember that families or other supporter may need support too. Education and resources can be critical to effectively participating in recovery activities.

- Formal person and family-centered planning can be a very useful process for helping people reengage and organize their goals and preferences, including areas of preferred relationships and roles if networks are depleted.

Reviewed Trainings and Resources as Part of the Person and Family-Centered Approaches in Mental Health and Co-Occurring Disorders Training Development Project

Introduction to this Resource List

This list was developed as part of a training project to help mental health professionals, practitioners, and others in the mental health community in Minnesota enhance their ability to deliver services in person and family-centered ways. The project included identifying what training and resources were already available in Minnesota and how well they might meet the needs of the mental health and behavioral health community. There was a special focus on those in Targeted Case Management roles. A standard protocol that included a review tool and at least two reviewers was used to ensure products were reviewed consistently. The following materials were reviewed and ranked as being likely to be helpful to Mental Health Targeted Case Managers or those in similar or related roles.

Materials Developed by The Learning Community on Person-Centered Practices

The Learning Community on Person-Centered Practices

TLCPCP is an organization and a global volunteer community. It focuses on supporting people who have lost or may lose positive control because of society's response to the presence of a disability or other conditions. It does so through training and development of person-centered practices. The Minnesota Department of Human Services Disability Services Division and other divisions have invested in disseminating training materials developed by TLCPCP. They have also supported development of trainers in Minnesota. The following two trainings are commonly available in the state. TLCPCP also supports other types of training. To locate trainings in Minnesota you can go to http://pct.umn.edu. Certified trainers are also listed on The Learning Community’s website. Some local trainings listed at the Minnesota site are free; others have a fee.

Person-Centered Thinking- Two Day Training (now modularized)

Person-Centered Thinking is equivalent to a full two-day training. Training is completed in groups. The terminology and strategies of this training are aligned with some state and national regulations in the area of person-centered practices. The curriculum is generic and skills are transferable to any setting including mental health settings. A wide variety of professionals could benefit from this training. This can include professionals from any scope of practice who:

- Are brand new to these skills and concepts.

- Want to understand these skills and concepts in a broader context than individual practice.

- Want to revisit these skills or expand their repertoire of strategies and approaches.

- Want to network with others in and out of their agency around these practices.

The concepts and strategies in this curriculum have meaning and are useful in mental health practices. However, the examples in the core curriculum focus mostly on adults, are not all mental health related, nor always current to the context of community living. Content does not explicitly support deeper understanding of equity or diversity issues and does not use examples that represent diversity. Though there is a small portion in the new version on culture, on the whole, the curriculum does not attend to these issues. In addition, there is no specific tie in to how to use these practices to ensure family-centered practices. Trainers in this curriculum have various backgrounds. It would be important to select a training with a strong background in mental health services and supports if that is an important training need for your group.

Picture of a Life Two-Day Training

Picture of a Life is two-day training that provides in-person learning and applying person centered thinking and planning tools to develop a person-centered description. The process is focused on helping a person envision the life they want in their community. The training include a co-trainer with support needs and others who are this person’s natural or paid supporters. Trainees get a chance to watch and participate in interviewing processes and enhance their discovery skills. Values of choice, control, direction, and shared power are modeled in the training.

The quality of the training is highly dependent on the skill and knowledge of the facilitator and the willingness of the co-training and supporters to share. Participants will likely benefit more if they attend a session where the co-trainers needs are similar to those of the populations they support. There will be no explicit connection to the mental health practices of recovery, peer support, or cultural and equity practices if the facilitator does not have these skills, knowledge, and orientations. Person-Centered Thinking (described above) is required training before attending Picture of a Life.

Person-Centered Counseling Training Program

The Person-Centered Counseling Training Program is a blended learning model that embeds the Person-Centered Thinking skills and planning skills into online modules. The target audience for this training is counselors through the Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs) and others who are engaging in development of No Wrong Door systems. The online component is available in Minnesota via DirectCourse. For full review for this audience please see description below. For more information on the in-person day of training, contact The Learning Community for Person Centered Practices.

Materials Available Through the DirectCourse

DirectCourse is a national online curriculum for direct support professionals and similar professionals who support people to live in their communities. It is available in Minnesota through support from the Department of Human Services. The training programs and curriculum are self-paced, competency-based, and multimedia. The following materials from DirectCourse were reviewed for the mental health community.

College of Recovery and Community Inclusion (CRCI)

This online training was developed by Temple University Collaborative on Community Inclusion of Individuals with Psychiatric Disabilities. It consists of approximately 38 hours of self-paced training for community based mental health workers. The set of available courses is listed below.

- Understanding Community Inclusion

- Cultural Competence in Mental Health Service Settings

- Introduction to Mental Health Recovery and Wellness

- Mental Health Treatments, Services and Supports

- The Effective Use of Documentation

- Universal precautions and Infection Control

- Seeing the Person First: Understanding Mental Health Conditions

- Professionalism and the Community Mental Health Practitioner

- Understanding the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

- Understanding Trauma and Its Impact

The courses in the College of Recovery and Community Inclusion can be helpful to any practitioners interested in recovery-based inclusion and self-determination models. The suite of courses in CRCI doesn’t use term “person-centered” but aligns with these approaches. They cover the scope of all mental health professionals. This material can be useful to support planners in mental health in apply the Minnesota Olmstead Plan expectations in their work. These courses consider culture and evidence-based practices. Incorporation of family into support is not included substantially.

The Minnesota Department of Human Services has purchased a limited amount of seats in Minnesota that are available for free. Contact Nancy McCulloh at mccul037@umn.edu. Rates for broader access will vary based on organization size. Information can be obtained by contacting Bill Waibel at Elsevier, b.waibel@elsevier.com.

Person-Centered Counseling (PCC) Training Program

These online materials were explicitly designed for the No Wrong Door System of Long Term Services and Supports (LTSS). It considers all populations, all ages, and all methods of payment for LTSS. Person-Centered Thinking and Planning skills are a core of the training program. There is a whole course on family caregiving and other lessons on family involvement. However, content is not strictly focused on mental health.

This content would be best for disability generalists who have a portion of their potential recipients living with serious mental illnesses. Another potential target audience is staff affiliated with Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics or Behavioral Health Homes or similar services, where clinicians and LTSS and community professionals need to have a coordinated understanding of person-centered practices across clinical and community settings. This curriculum needs to include a one-day in-person training in PCT to be considered complete as far as PCT skills. It would need a skilled training to support groups in organizing a blended learning model for above purposes. It is not ideal as core training for MH TCM because of the more broad disability focus but is rooted in recovery principles, self-determination, and culturally responsive services.

The Minnesota Department of Human Services has purchased a full contract for this curriculum in Minnesota that makes training available for free and/or with minimal administrative costs. Go to: https://mn.gov/dhs/partners-and-providers/training-conferences/directcourse/to learn more.

Materials through the Yale Program for Recovery and Community Health

The Yale Program for Recovery and Health, Person Centered Approaches has a focus on research, consultation and tools in the area of person-centered approaches in mental health and co-occurring disorders.

The following resources related to authors and researchers at this program were reviewed.

Partnering for Recovery in Mental Health: a Practical Guide to Person-Centered Planning

Partnering for Recovery in Mental Health is a practical guide for conducting person and family-centered recovery planning with individuals with serious mental illnesses and their families. This guide represents a new clinical approach to the planning and delivery of mental health care. It emerges from the mental health recovery movement, and has been developed in the process of the efforts to transform systems of care at the local, regional, and national levels to a recovery orientation.

This is a very solid and recommended resource that looks comprehensively at person and family-centered practices in planning specific to mental health conditions and co-occurring conditions. It provides context to recovery, self-determination, cultural needs, family support, and shared power. It is a good overall resource that would be helpful to any professional working with people with serious mental illnesses and required to complete support or treatment plans, including targeted case managers.

This book is authored by Janis Tondora, Rebecca Miller, Mike Slade and Larry Davidson and was published in 2014 by Wiley-Blackwell. It is available online as an ebook or from booksellers in hard copy, for an approximate cost of $42.00.

Getting in the Driver’s Seat of Your Treatment: Preparing for Your Plan

This resource is a downloadable booklet for organizing information a person might want in a treatment or support plan. It is meant to help people organize their thoughts and information in ways that are likely to yield person-centered goals and approaches in a treatment plan.

The strengths of this resource include: It is easily downloadable from a public site. It is concrete, process-oriented, flexible and applicable to many circumstances, and written in plain language. It gives people structure and context to taking the time to identify their goals and preferences in key areas outlined in the Person-Centered Informed Choice Protocol (DHS, 01/17). It asks people to consider including people important to them in the process. It would be a great foundation for developing a person-centered plan. Professionals and practitioners for all level of practice in mental health would benefit from being familiar with this tool. Case managers, support planners, and those in similar roles would benefit the most. There is a Spanish language version available.

Limitations of this resource include: The rights information is specific to the state of Connecticut (but could be easily customized to Minnesota). It provides little context for bigger picture aspects of history and professional responsibly. While it may work with a variety of cultures and circumstances, it does not support practitioners in how to adapt for a variety of cultures and circumstance. Family and natural supporters are considered as support but not as people who may need support. Information would need more work to translate into an operational treatment plan. Literacy would be an issue with this tool if used without assistance.

Authors are Tondora, Miller, Guy and Lanteri. Published in 2009 by Yale Program for Recovery and Community Health.

This online resource is available as a .pdf document at no cost:

Materials Offered Through the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery

The Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery promotes mental health recovery through education, training, and research based on WRAP©. (Wellness Recovery Action Plan). It is a peer run, non-profit organization that provides training, consultation, and program activities to support the wellness, recovery, community inclusion and peer support journeys of individuals. They work with the owners of WRAP© materials at Advocates for Human Potential (AHP) to ensure the fidelity and quality implementation of WRAP© Facilitation in the health care system. There are a variety of training and consultation options offered through Copeland.

Locally people can connect and take seminars through the Kaposia which is an International WRAP© Center for Excellence.

Seminar I: Developing Your Own WRAP©

The Developing Your Own WRAP© workshops is co-facilitated by WRAP© Facilitators in a variety of formats and agendas, including 8-12 week WRAP© groups, 2-3 day workshops, retreats. Participants in these workshops will learn how to develop their WRAP© as a personalized system to achieve their own wellness goals. These workshops are for anyone and can apply to any self-directed wellness goals. WRAP© is a safe, effective wellness process that has an evidence-base for supporting mental health recovery. It is s self-directed, peer supported process that the person engages with in ways that they prefer. WRAP© is an ongoing processes of reflecting on and engaging approaches and lifestyles that support personal wellness. Processes can be used by individuals and organizations to move to a true recovery and self-determination focus in services and supports. WRAP© has proven to be an effective approach to working with children, youth, and families and caregivers to improve relationships, feel more hopeful, create support systems, learn to self-advocate, and put a greater focus on their personal overall wellness.

WRAP© must be delivered with fidelity in order to meet the evidence based criteria. This include that participation in WRAP© be completely voluntary, that at least two peer facilators who are skilled, trained, and mentored facilitate this process, materials are appropriate, and all processes align with the values and ethics of WRAP©. (To learn more about fidelity download and read the document The Way WRAP Works!.) Professional who have their own WRAPs can benefit from the process and also understand the value and power of WRAP© in supporting recovery.

WRAP© is voluntary, focused on wellness, owned by the person, and avoids clinical or medical language. It is a powerful tool for helping people reconnect with hope, personal responsibility, and personal strategies for recovery. However, it is not something professionals can have access to without a person’s permission and it is not something professionals can require of people. If people chose to complete a WRAP© on their own, it can support their ability to more clearly define many of the aspects of the PCICTP. It is something to recommend, especially to people who have lost touch with what recovery and a life worth living means to them. However, there can be no expectation that people participate unwillingly or in order to receive services.

The cost for this entry course ranges from $100-400.00 approximately. Locally, there may be a possibility for a need-based reduction in the fee or waiving of the fee.

References

- Bourne, M.L., & Smull, M.S, (2018). Person Centered System Change: Thinking about Risk When People Want to Be Connected with their Community.Charting the Course Together: Next Steps in Becoming a Person-Centered System (October 9th&10th). Minneapolis, MN.

- Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery. (2014). The Way WRAP Works!Retrieved April 17, 2018, from:https://copelandcenter.com/sites/default/files/attachments/The%20Way%20WRAP%20Works%20with%20edits%20and%20citations.pdf

- Mental Health & Stigma. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/why-we-worry/201308/mental-health-stigma

- Minnesota Department of Human Services. (2010). Adult Mental Health - Targeted Case Management Introduction AMH-TCM. [online training module]. Retrieved from Minnesota Department of Human Services TrainLink: www.dhs.state.mn.us/TrainLink/.

- Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 11, 2016). Lead Agency Requirements for Person-Centered Principles and Practices – Part 1 – An introduction to the requirements for person-centered principles and practices. http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/publications/documents/pub/dhs-285572.pdf

- Minnesota Department of Human Services. (March 4, 2016). Lead Agency Requirements for Person-Centered Principles and Practices – Part 2- Information to lead agencies about the Person-Centered, Informed Choice and Transition Protocol.http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/publications/documents/pub/dhs-285935.pdf

- Minnesota Department of Human Services. (May 25, 2016) Lead Agency Requirements for Person-Centered Principles and Practices – Part 3- Information to interested stakeholders about DHS protocols for monitoring lead agency compliance with the Person-Centered, Informed Choice and Transition Protocol. http://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/publications/documents/pub/dhs-287420.pdf

- Minnesota Department of Human Services’ (DHS) (March 27, 2017).Person-Centered, Informed Choice and Transition Protocol.Retrieved April 17, 2018, from https://mn.gov/dhs/partners-and-providers/program-overviews/long-term-services-and-supports/person-centered-practices/pc-ic-tp-faq/https://edocs.dhs.state.mn.us/lfserver/Public/DHS-3825-ENG

- Minnesota’s Governor’s Task force on Mental Health. (November 16, 2016). Governor’s Task Force on Mental Health: Final Report.St Paul, MN. Retrieved from: https://mn.gov/dhs/assets/mental-health-task-force-report-2016_tcm1053-263148.pdf

- O’Brien J (1989) What’s Worth Working For? Leadership for Better Quality Human Services. Georgia: Responsive Systems Associates.

- O’Brien, J. & Lyle, C. (1987).Framework for Accomplishment. Lithonia, Ga.: Responsive Systems Associates.

- Olmstead Implementation Office. (March, 2018). Putting the Promise of Olmstead into Practice: Minnesota’s Olmstead Plan.St Paul: MN https://www.dhs.state.mn.us/main/groups/olmstead/documents/pub/dhs-299180.pdf

- Perlick, D. A., Rosenheck, R. A., Clarkin, J. F., Sirey, J. A., Salahi, J., Struening, E. L., & Link, B. G. (2001). Stigma as a Barrier to Recovery: Adverse Effects of Perceived Stigma on Social Adaptation of Persons Diagnosed With Bipolar Affective Disorder. Psychiatric Services,52(12), 1627-1632. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1627

- Rapp, C., & Goscha, R. (2011). The Strengths Model: A Recovery-Oriented Approach to Mental Health Services. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sauer Family Foundation. (n.d.). Minnesota's System of Care Grant for Children's Mental Health.Retrieved fromhttps://www.sauerff.org/blog/2017/08/14/minnesotas-system-of-care-grant-for-childrens-mental-health/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (nd). Evidence-Based Practices Resource Center.Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/ebp-resource-center

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018).Focus on holistic definitions of wellness (using SAMHSA 8 dimensions framework).Retrieved April 17, 2018, from https://www.samhsa.gov/wellness-initiative/eight-dimensions-wellness

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (May 5, 2016) Increasing Access to Behavioral Health Services and Supports through Systems of Care. Short report.https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/childrens_mental_health/awareness-day-2016-short-report.pdf

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014) SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach.HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (05/17/2016.) Person- and Family-centered Care and Peer Support. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/section-223/care-coordination/person-family-centered

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). The Eight Dimensions of Wellness. https://www.samhsa.gov/wellness-initiative/eight-dimensions-wellness.

- The Fulcrum Publishing Society.(March 15, 2017). Mental health is intersectional. Retrieved from http://thefulcrum.ca/features/mental-health-intersectional/

- TLCPCP (2016). Person-Centered Thinking(2 day training). The Learning Community for Person-Centered Practices. http://tlcpcp.com/

- The World Health Organization. (nd.) Taking Action to Improve Health Equity. The Social Determinants of Health. Action on Social Determinants of Health. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/action_sdh/en/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health (2011). National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. Retrieved from https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/pdfs/EnhancedNationalCLASStandards.pdf

- United States. President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. (2003). Achieving the promise: transforming mental health care in America: final report.[Rockville, Md.]: President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/mentalhealthcommission/reports/reports.htm

Credits

The content of materials developed through this contract was co-created with members of Minnesota’s communities. Co-creation include structured and open-ended conversations as well as listening sessions. It also included seven structure co-creation processes conducted in different parts of the state. These sessions include professionals and people with lived experience or their families. Community members were also invited to review and edit the content of online materials (Community Reviewers). Participants were kept informed about ongoing progress through a website.

The following sessions helped to shape refined definitions and areas of focus after the initial environmental scan was complete.

- African Mental Health Summit (2017)- Open-ended conversation with a large group regarding goals, definitions, and gaps.

- American Indian Mental Health Conference (2017)-Structured conversation with a smaller group around goals, definitions, and priorities.

- DHS Mental Health Division –Structured conversation with a larger group around definitions and priorities.

- Parent Catalyst Leaders Group (Hennepin County) – Listening session with parents who were newer to the system and guided by more experienced parents around gaps and challenges.

There were seven (7) Co-Creation Groups (in 6 communities) Rochester, Duluth, Mahnomen, Minneapolis, St Paul (2), and New Brighton. A total of 89 people participated in these groups. Participants included a spectrum of people with a variety life experiences and backgrounds. These processes were developed to support the maximum engagement of each participant. The following people attending a co-creation session:

- Thomas Anderson, Minneapolis

- Laura Armstrong, Minneapolis

- Mina Blyly-Strauss, Minneapolis

- Carol Brogan, Chatfield

- Brenda Caya, Duluth

- Mary Chazen, St. Paul

- Rose Chos, Duluth

- Cristina Combs, St. Paul

- Jennifer Conger, Savage

- Heidi Crees, Minneapolis

- Debbie Crittenden, Bloomington

- Tom Crittenden, Bloomington

- Nicole Duchelle, Lake City

- Polina Duchelle, Lake City

- Amber Dukowitz, Duluth

- Josephine Eades, Duluth

- Karen Ellian, Duluth

- Feisal Elmi, Minneapolis

- Angela Elwell, Eagan

- Amelia Fink, St. Paul

- Kassandra Flake, Minneapolis

- Mike Francis, Eagan

- Carl Gardner, Minneapolis

- Colleen Garman, Minneapolis

- Gerald Geist Jr., Moorhead

- Cathy Gillman, Cottage Grove

- Triasia Givens, Minneapolis

- Susan Govern, Minneapolis

- Amy Granquist, Duluth

- Jane Haas, Stillwater

- Kristin Hale, Duluth

- Ricky Hamm, Rochester

- Keven Hardy, Rochester

- Tom Haselman, Minneapolis

- Vivian Henry, St. Paul

- Jenny Isaacson, Duluth

- Melissa Johansson, Maplewood

- James Johnson, Duluth

- Carolyn Keefner, Westminster, Co.

- Jessica Kisling, Minneapolis

- Bob Klade, McIntosh

- Kay Knight, Duluth

- Fonda Knudson, Fergus Falls

- Jeanne Kolo-Johnson, Moorhead

- Maggie Lemasters, Duluth

- Jenny Linder, Duluth

- Tulu Lope, Inver Grove Heights

- Ginger Madeiros, St. Paul

- Diane Marshall, St. Louis Park

- John Martin, Minneapolis

- Kristy Matzke, Rochester

- Lamont Mayo, Minneapolis

- Nick Mazzoni, Duluth

- Alvin McCoy, Minneapolis

- Willard McDonald, Rochester

- Kurt Meyer, Minneapolis

- Cari Michaels, St. Paul

- David Moses, Rochester

- George Nadeau, Minneapolis

- Beth Nelson, Fergus Falls

- Richard Oni, Birchwood

- Peggy Ostman, Duluth

- Jovi Parm, Minneapolis

- Rose Plentyhorse, Minneapolis

- Tyler Rinta, Minneapolis

- Ruby Rivera, St. Paul

- Michael Ruhl, Minneapolis

- Ryan Sandquist, Minneapolis

- Julie Scharver, Fergus Falls

- David Schreyer, Two Harbors

- Kelsey Shoden, Rochester

- lenda Smith, Fergus Falls

- Cora Spear, Burnsville

- Jennifer Thomas, Maple Grove

- Nelly Torori, St. Paul

- Maria Tripeny, Bloomington

- James Van Druten, Duluth

- Sarah Vinueza, Minneapolis

- Kenya Walker, St. Paul

- Claudia Waples, South St. Paul

- Eileen Ward, West St. Paul

- Terry Wasnick, Duluth

- Linda Weber, Rochester

- Bryant Wheeler, Minneapolis

- Tobias Wilde, Moorhead

- Shannon Williams, Duluth

- Tera Wiplinger, Rochester

- (Wendy) Maxuan Wu, Minneapolis

- Ann Zick, Osage

The authors for the online lessons were:

- Susan O’Nell, Project Director

- Jody Van Ness, Project Staff

- Merrie Haskins, Project Coordinator

There were seven community reviewers recruited to review the content of online materials that were developed. These reviewer were mental health professionals and included family members of service users. The following people served in this role:

- Allison Brockway – Sherburne County

- Tamba Gordon – Hennepin County

- Tom Haselman – Hennepin County

- Jessica Kisling – University of Minnesota

- Jane Lawrence – Community Reviewer

- Jeff Olson – Headway Emotional Health

- Dorothee Tshiela – Face to Face Health and Counseling

In addition Darrin Helt of the DHS Behavioral Health Division served as editor and approver.

Web development, design, and media team:

- Amanda Webster

- Shawn Lawler

- John Westerman

- Kristin Dean

- Sarah Hollerich